IT’S THAT TIME! No, not Mariah Carey Christmas time, though I suppose it’s that, too. I’m talking about Sagittarius season, aka The Best Season. From now until the Winter Solstice on December 21, I’ll be offering 20% off annual subscriptions. This is a great time to upgrade if you’ve been considering it!

I am a full-time freelance writer. Paid subscriptions to this newsletter allow me to dedicate more time to this work, as well as to pay an editor to help me with this newsletter.

I have left X completely but you can find me on Bluesky, if that’s your thing. Below, a rant about the framing of some recent news stories, plus a bonus rant and a link roundup for paid subscribers.

haterade: a failure to complicate the narrative

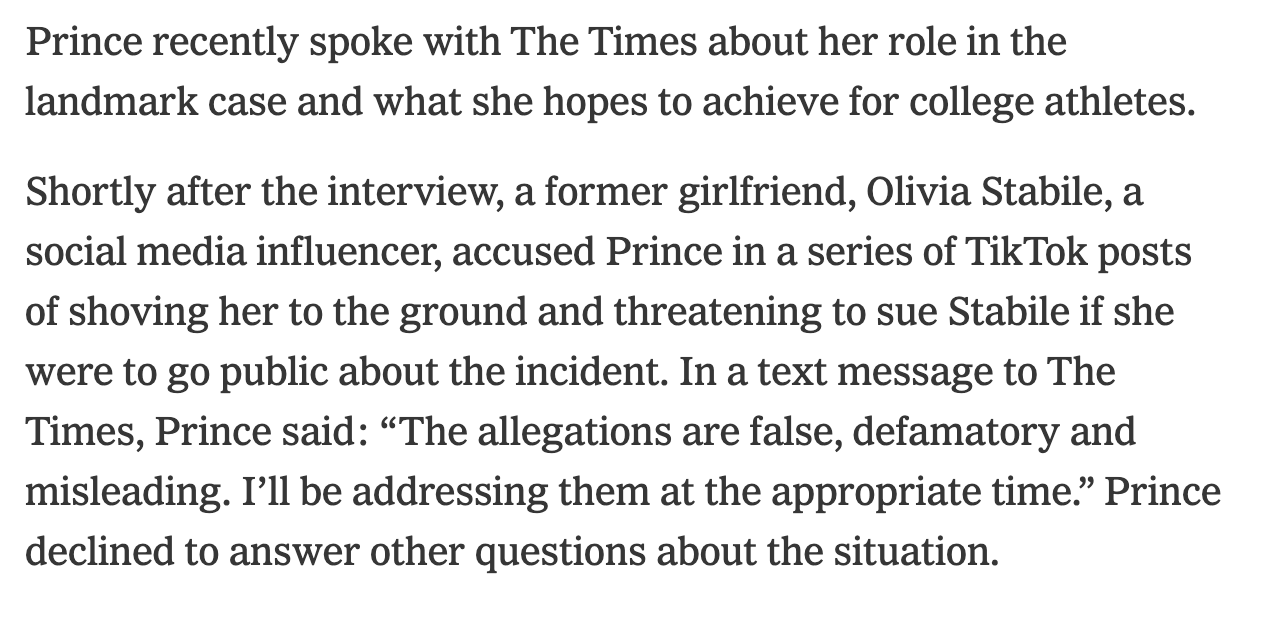

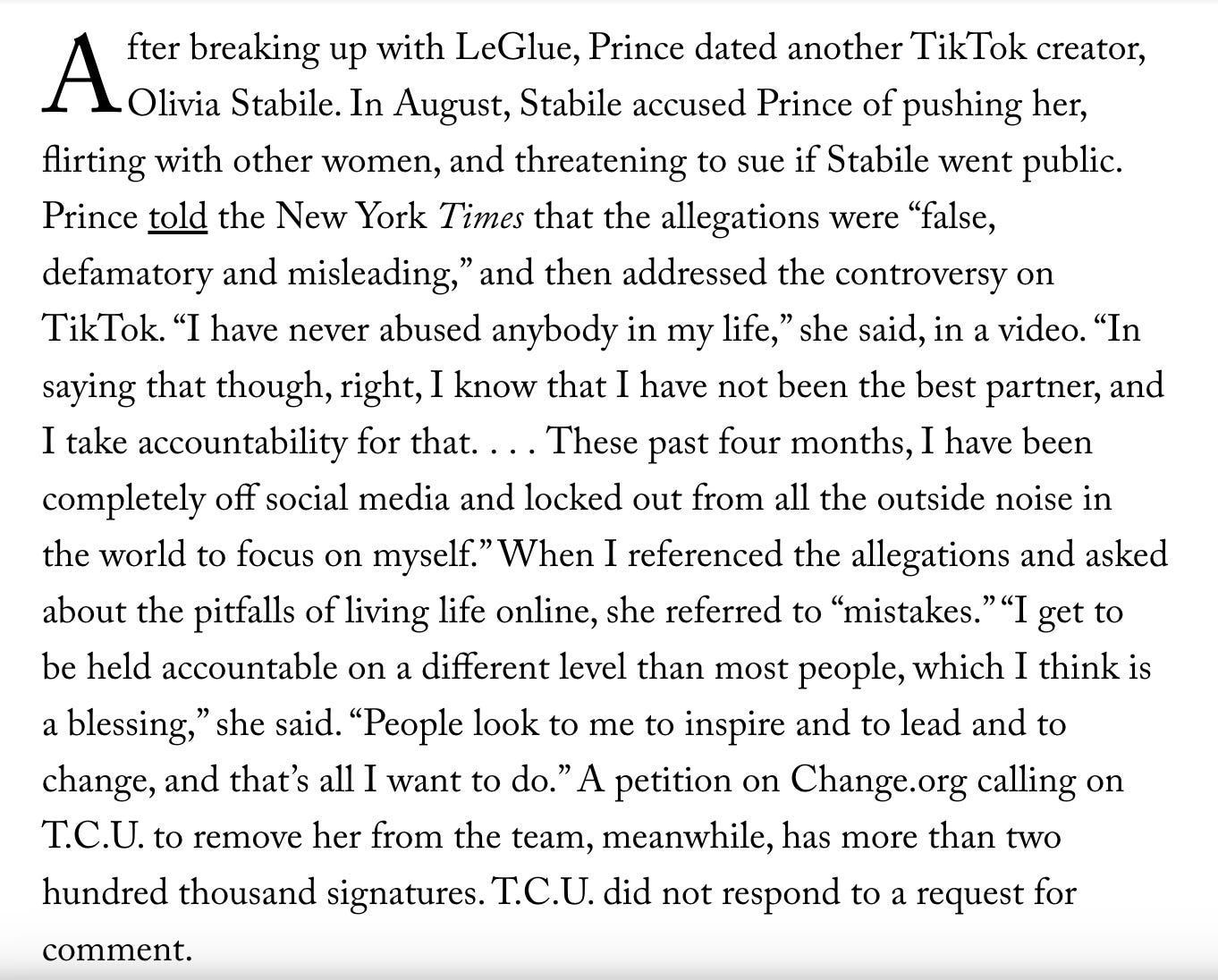

I’ve been looking for a way to talk about the recent coverage in mainstream outlets of Sedona Prince and her role in a landmark lawsuit to get college athletes paid. She was the subject of a recent interview in the New York Times, as well as a Louisa Thomas profile in The New Yorker. Both stories ran after several ex-girlfriends of Prince went public with allegations of abuse during their relationships, and neither story manages to grapple with the subject at all. They each do the very basic due diligence of mentioning that these allegations exist—each with a single paragraph and a statement of denial from Prince.

Oddly enough, it wasn’t until last week’s Vanity Fair profile of Augusta Britt, Cormac McCarthy’s 16-year-old “muse,” essentially broke the literary internet that I understood what all these stories had in common that bothered me so much. Both stories about Prince, as well as Vincenzo Barney’s profile of Britt, fail to effectively complicate the narrative regarding situations that have a whole lot of gray in them.

In the case of Prince, it’s true that her impact on collegiate women’s athletics is one that we still can’t fully measure. She posted the viral and now infamous video from the 2021 NCAA women’s tournament (which, at the time, could not legally use the “March Madness” branding; that was only for the men’s tournament) showing the lack of resources the women received. The response to that video was massive, and resulted in almost-immediate changes. Just three years later, the 2024 women’s March Madness championship viewership far surpassed the viewership for the men’s championship game. It’s likely that doesn’t happen—at least not so quickly—without Prince’s video.

Now Prince is named as a plaintiff in arguably one of the biggest—if not the biggest—lawsuits against the NCAA, one that could change the material reality for college athletes in the future. While NIL did some of that, only the biggest names really benefit from those deals. What about the majority of college athletes, who give their time, body, and livelihood to sports and never see a monetary benefit?

No one is arguing with Prince’s significance when it comes to the labor and working conditions of these athletes, and she deserves credit for being willing to put herself out there and challenge an unjust system, for not being satisfied with the crumbs she—and other athletes—are given. But that is not the only impact that Prince has had on the culture. You cannot separate the Prince who has become the face of the college athlete-as-worker from the Prince who has 2.5 million followers on TikTok, allegations of mistreatment from multiple girlfriends, and was the subject of a petition with over 200,000 signatures asking TCU to remove her from the basketball team.

Prince is all of these things. And any profile of her needs to grapple with that. It needs to feature the voices and stories of her exes, or at least attempt to corroborate them. It needs to ask how these allegations impact the legacy that Prince could leave. Instead, we get this, from the New York Times:

And this, the second-to-last-paragraph in a 2,600-word profile from The New Yorker:

Frankly, that’s just not good enough. Arguably, it’s journalistic malpractice. As was Vanity Fair’s handling of the Augusta Britt story. Barney, who discovered this story after Britt commented on his Substack review of two of McCarthy’s novels (you can’t make this shit up), wrote the feature in what he referred to as his “bold, nonsensical style.” And while the prose itself has gotten a lot of attention, so too has his framing of the story, which romanticizes the relationship between a 16-year-old Britt and a 42-year-old McCarthy.

“I’ve been surprised that so many responses have passed over Augusta’s valuation of herself,” Barney said in an interview with Slate. “Let us remember, Augusta Britt continued to age and is no longer a teenager but a 65-year-old woman who has had her entire life to reflect on McCarthy, and used her agency several times in their relationship, including leaving McCarthy after finding out he was still married and had a child. Still, it is a charged question. Grown men having relationships with teenage girls is immoral, as is writing sexually explicit letters to them. As I write in the piece, it was also illegal.1 But I am also deeply uncomfortable contravening a woman’s authority on her own life. Especially as a young man half her age. She has been emphatic that there was no grooming (as recently as again today).”

I think it’s entirely correct not to define the nature of a relationship for someone, especially if they don’t see themselves as a victim. But it’s also true that one of the fundamental features of an age gap relationship in which this kind of grooming occurs is that the teenager sees themselves as having much more agency than they actually do. This is actually one of the textbook effects of grooming. There has to be a way to grapple with the complexities of this story without discrediting the experience of the subject at the center.

“[Barney] wasn’t the writer to grapple with these weighty issues,” Dan Kois wrote at Slate. “I don’t know who would be! But it wasn’t a guy so determined to make his mark on the literary firmament that he eclipsed his subject’s story with his own writing style.”

Because that’s the thing about stories: none of them are ever simple. Life is not a superhero film in which the heroes and villains are always clear cut, or the victims are entirely helpless. Life contains shades of gray and those nuances and conflicting truths are what make stories good. They’re also what make them real. Oversimplifying the truth of a story does a disservice to everyone involved, but almost always disproportionately impacts those who were most harmed by a situation.

By erasing the victims of Prince’s actions from the profiles written about her, or refusing to grapple with the fullness of the reality of Britt’s victimhood at the hands of McCarthy, the only people who gain anything are the perpetrators of harm—Prince and McCarthy (or, in this case, McCarthy’s legacy). As journalists, our job is to uplift the voices of the marginalized as much as possible. And that doesn’t have to mean flattening the truth (after all, Prince is a lesbian who deals with her own forms of marginalization—but in the context of her relationship with these other women, she is the one with more systemic and cultural power), it just has to mean acknowledging it.

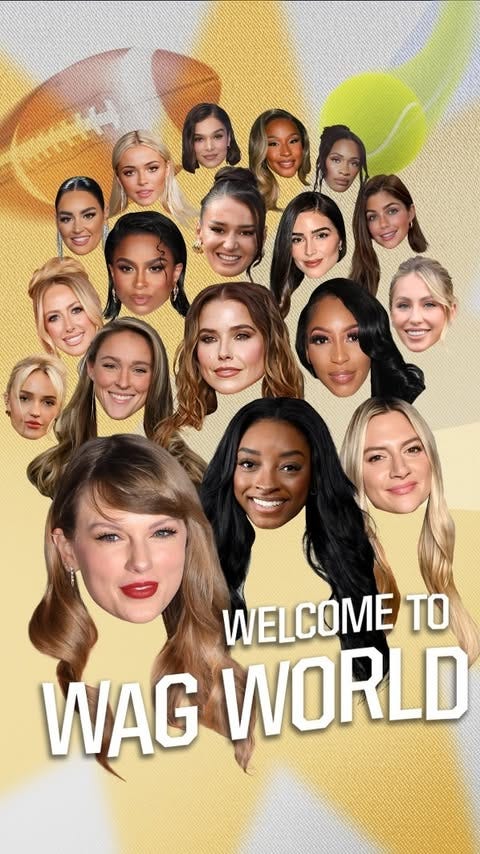

a mini rant: quasi-erasure of queer WAGs

Glamour released a package of stories as part of “WAG Week,” looking at WAGs as cultural trendsetters. “The genesis of the project was this: I saw the impact WAGs were having on social media and real life, and knew we needed to dig deeper,”

writes of the project. “What resulted is an entire five days of content, 19 separate stories, dozens of interviews, and even more fun social moments.”Now, I do think this package is dope and otherwise well-done, and I love seeing WAGs celebrated as part of sports culture. I especially loved this

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Out of Your League to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.