we need to talk about weight loss drug ads in women's sports

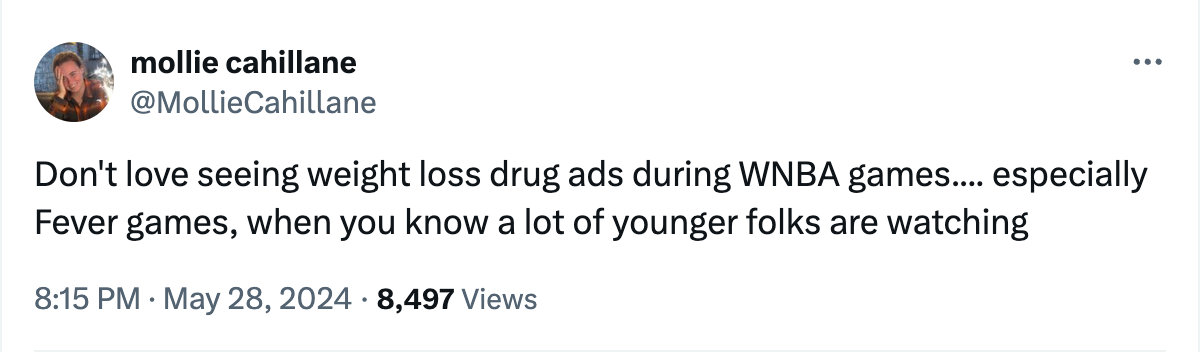

Women's sports also have a rapidly growing audience, and brands are desperate to cash in.

Thank you so much for being here! I am a full-time freelance writer and paid subscriptions to this newsletter allow me to continue to do work like this, including hiring an editor to help me with reported content like today’s post. You can upgrade here:

I have a bunch of new people here this week, thanks to my appearance on the Burnt Toast podcast with . We chatted about a bunch of things, including the issue of weight loss drug ads running during women’s sports events and why it’s even more insidious than it might appear at first glance. You can listen to our conversation here.

Below, a more in-depth investigation into the issue.

we need to talk about weight loss drug ads in women's sports

Weight loss drugs like Ozempic, Mounjaro, and Wegovy (also known by the generic name of GLP-1s) have surged in popularity over the last several years. Advertising spending on these drugs topped $1 billion in 2023—a 250% increase YoY—and some of those ads have been spotted during women's basketball games (NCAA, WNBA, and Unrivaled) over the past few seasons, whether it's a ro ad during a Sunday Sun/Sky game on NBC Sports, a commercial for HERS injectable compounded semaglutide during Unrivaled’s opening broadcast on TNT, or a Lynx partnership with Livea, a weight loss program based in the Midwest.

And while some people need these medications to treat certain conditions, advocates have criticized the use of these drugs for weight loss alone. These medications have serious and life-threatening side effects. They also promote and uphold fatphobic body image ideals that lead to disordered eating and poor body image among women and girls. Medical and advertising regulatory organizations have also raised alarms over the lax oversight regarding these ads and the harm they could do to patients.

What are the drugs?

GLP-1s are intended to treat conditions like diabetes. But their “off-label” use is for weight loss. Ro, for example, explicitly advertises its GLP-1 medication as being for weight loss, as does HERS.

In order to sell a treatment, you must sell a disease. “You market a treatment by convincing doctors and patients to diagnose the illness that your drug or procedure treats,” writes Carl Elliott in his essay “Pharmaceutical Propaganda” from the book Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality. In the case of these drugs, they’re selling ob*sity.

Eli Lilly, the company behind Mounjaro and Zepbound, is the Indiana Fever's "jersey patch and health equity partner." The company had an ad campaign that cautioned against using these drugs for purely aesthetic reasons, saying, “Some people have been using medicine never meant for them—for the smaller dress or tux, for a big night, for vanity.” The implication is that the drugs are meant for people who “need” them, and the people who “need” them, the ad specifies, are “people whose health is affected by ob*sity.”

I want to be clear that semaglutides and other GLPs do offer significant health benefits to folks with diabetes and other metabolic conditions—this is not what I’m talking about. The ads for these weight loss drugs aren’t talking about diabetes as the presenting condition, they’re talking about being fat as the presenting condition. This is the difference between marketing for a medical condition and marketing by fear mongering about body size.

The Lynx’s partnership with Livea, announced in 2022, was presumably about “health”: “Livea is committed to transforming lives in the community through nutrition education, lifestyle guidance and one-on-one support,” the press release read. “The partnership will focus on living a well-rounded and healthy lifestyle.”

But scroll to the bottom and read the fine print and you’ll find this:

“We understand the psychology behind proven and effective weight loss that lasts! Receive the kind of personal accountability that no other program offers, why? Because you’re worth it! Livea – voted Best Weight Loss Program – with 10 locations throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin and online support options.”

On the Livea website, Lynx coach Cheryl Reeve is listed as one of the brand ambassadors, her headline proclaiming, “10 lbs in her first 4 weeks!”

“When we see ads for specific medical conditions, we understand that if we don't have the medical condition in question, we don't need to buy the product,” says

, the author of Fat Talk: Parenting in the Age of Diet Culture and the Burnt Toast newsletter. “But weight loss drugs are marketed to everyone — even when the manufacturers talk about treating ob*sity as a medical condition (a status that's not evidence-based), we know how to translate that to mean ‘we could all stand to get thinner.’ So weight loss drug advertising truly isn't about health; it's marketing diet culture and anti-fat bias for profit.”Why women’s sports?

Weight-loss drug manufacturers likely assume that people who watch sports, particularly women who watch sports, are going to be more health-conscious than the average person. And in our culture, we associate “health” with “thinness.”

As Sole-Smith notes, the media also has had a direct impact on this framing of “sport” and “wellness,” over a period of decades. For a long time, coverage of women’s sports was folded into “fitness” coverage, and “fitness” coverage often brings elements of diet and beauty culture with it. Think about the difference in content in magazines like Women’s Sports and Fitness, versus a sports magazine geared towards men, like Sports Illustrated.

Women's sports also have a rapidly growing audience, and brands are desperate to cash in. Note: it’s not the leagues who accept these commercials (team sponsorships are a different thing altogether). Commercials are purchased through buying ad inventory from networks and streaming platforms (this was confirmed to me by ro and by the league). Brands can choose what events they want to market during based on the demographics for those events.

In women's sports, advertisers have access to a highly motivated market. Research has found that WNBA and women’s sports can “enhance a brand’s image by demonstrating its commitment to social responsibility, gender equality, and empowerment.” When a company advertises with one of these leagues, those values become associated with their brand, too. Nielsen’s Fan Insights found that 44% of WNBA fans have visited a brand’s website after seeing WNBA sponsorships during a game and 28% have bought from a sponsoring brand. Ads aired during the 2024 WNBA regular season through the end of May were a remarkable 26% more likely to spark consumer engagement than the 2023 WNBA season average. And women athletes are far more likely to convert buyers than their male counterparts, with a new study revealing that U.S. consumers are more likely to purchase sports tech products from Caitlin Clark, Simone Biles, and Serena Williams over comparable male athletes.

Fans assume they can trust a brand that their favorite women’s sport athlete has aligned herself with. And with research that has shown that despite the massive marketing push, most Americans say they wouldn’t consider taking a GLP-1 to meet their weight loss goals, perhaps drug manufacturers are hoping that they can leverage consumer trust in women’s sports leagues and athletes to change the public’s minds.

Why does this matter?

So many women’s sports revolve around the narrative that they are inspiring young girls watching at home. This appeal to youth is intentional.

“For us, it's really important to create products specifically for girls because we're trying to focus on keeping girls in sport.” Colie Edison, the WNBA's Chief Growth Officer, told PEOPLE last year. “The research shows us that girls drop out at a rate of two times faster than boys by the time we're 14. So finding ways to keep girls in sport, to empower them, is really important to the WNBA.”

The girls that Edison says the WNBA is trying to keep in sports are also highly susceptible to suffering negative consequences from advertising. World Health Organization data showed that girls don't receive the recommended amount of daily exercise, which it attributes to body image concerns causing girls to drop out of sports. That data was the catalyst for Dove's (in partnership with Nike) Body Confident Sport campaign. That campaign was advertised often during ESPN’s coverage of the women’s March Madness tournament last year (alongside the weight loss drug ads lol). “We know movement is beneficial for overall health,” writes

at the Parenting Without Diet Culture newsletter, “but it’s not hard to hear, lurking under the surface, the very fatphobia that contributes to the body image problem this program is trying to address.”Recent data shows that girls ages 12-18 are the fastest growing market for women's sports, which makes these weight loss drugs especially concerning. This is the age group most vulnerable to the onset of eating disorders (the median age of onset is 12.6 and over a million American teenagers develop eating disorders before they turn 21).

“Watching women's sports can already be activating for some folks dealing with eating disorders or just subclinical body stuff—you're watching elite athletes with bodies that are not like our mortal bodies, doing all these incredible physical acts,” says Sole-Smith.

“It's amazing, obviously, but it can also trigger comparison in unhealthy ways. I would imagine that the weight loss drug manufacturers are aware of this on some level, and that's why advertising during these games is appealing to them—they're reaching an audience that may already be questioning their body's value in some way just by [nature] of the activity they're participating in.”

Use of weight loss medications among teens is skyrocketing, too—the number of prescriptions for GLP-1 weight loss medications in that age group rose from 8,000 to more than 60,000 between 2020 and 2023. And according to data published in May in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 60% of the young people being prescribed GLP-1 medications are girls.

Again, GLP-1 prescriptions treat more than weight loss, including hormonal and insulin-related conditions like PCOS, according Dr. Melanie Cree, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado. But these drugs are also being used to treat ob*sity on its own, too.

Dr. Caren Mangarelli, a pediatrician who works with the Lurie Children’s Hospital's Pediatric Wellness & Weight Management Program, told ABC News that she believes the medications are only reaching a small percentage of teens “who could potentially benefit from the drug, whether for type 2 diabetes and/or obesity,” citing the statistic that “nearly 20%, or around 14.7 million children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 in the U.S. are considered obese, according to the CDC.”

According to Sole-Smith: “This is an age range that needs better information about the serious health consequences that come with dieting and disordered eating behaviors; they don't need to be sold drugs that may or may not benefit their health on the promise of thinness.”

The marketing behind GLP-1s would be problematic in any context. But their association with women's sports only amplifies the negative effects. Leagues like the WNBA may be sincere when they say they're trying to inspire girls and young women with athletes in a wide range of bodies doing incredible feats night after night. But a lot of that good work is undone when in between action, those vulnerable viewers are bombarded by ads selling self-consciousness and body anxiety.

“Young people will suffer disproportionately from the collateral damage that comes with relentless marketing of these drugs,” writes Oona Hanson at her newsletter Parenting Without Diet Culture. “Kids are coming of age surrounded by increasingly lucrative anti-fatness, a proliferation of before-and-after photos, and the normalization of severely restricted eating.”

This story was edited by Louis Bien.

I wonder if there will be any backlash. On a similar note I've fully stopped listening to podcasts that had Noom ads. I know the Eli lily patch on the fever jerseys annoys the hell out of me. Would stop me from buying a jersey if I was a fever fan.

I really loved this conversation between you and Virginia, and appreciated the insight about the ad buys. I've been home recovering from surgery the last couple of weeks and watching more TV than usual and it's just been.... non-stop pharmaceutical ads, of which probably 80% are for glp-1s. I really don't think there should be pharma ads or marketing, period; i'm curious how the placements during womens' sports compares to advertising across the board or in other media verticals.